Today, the old quarries have become adventure tourism sites which offer a variety of activities.

The biggest and most wellknown quarries are located close to the promontory Hammerknuden: Hammerværket and Moseløkken.

But there were many small - and essentially privately owned - quarries scat-tered around the large estates in the north of Bornholm.

The stone blocks from Hammerværket and Moseløkken were transported to Allinge Harbour and mainly shipped onwards to Copenhagen and Germany.

The stone blocks from Hammerværket and Moseløkken were transported to Allinge Harbour and mainly shipped onwards to Copenhagen and Germany.The stone blocks were also transported to the harbour of Hammerhavn as well as Vang Harbour, where they were further refined before being shipped out.

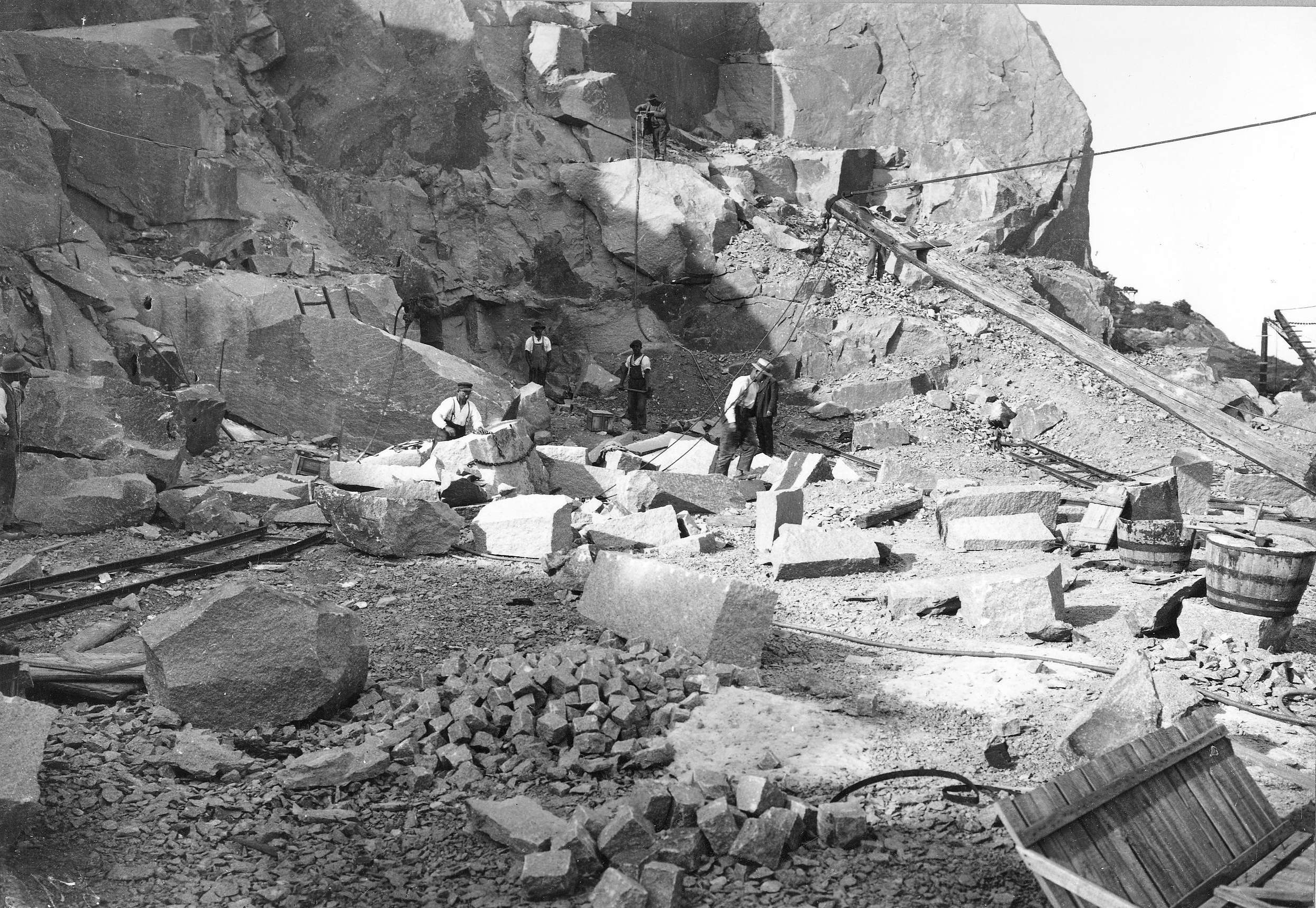

Stories of hardworking quarrymen who hewed holes into the rock, filled them with gunpowder and blasted large blocks loose.

They would then use their strength to manually drive in wedges and split the blocks into kerbstones and cobblestones or building blocks, which were refined by others and used for the construction of bridges, castles, lighthouses or fountains.

It also holds the story of a poor municipality that sold the Hammerknuden promontory to German entrepreneurs, who mechanised the quarrying operations.

Compressed air, tipping lorries and conveyor belts turned the granite quarries into highly productive ventures, and the Germans also established a harbour - Hammerhavn - from which ships laden with kerbstones and cobblestones for Germany’s growing road network would depart on a daily basis right up until the outbreak of the First World War.

Hammerknuden also holds stories of its own.

A story of the promontory coming back under Danish ownership, national sentiments and a dream of turning the breathtaking landscape into a protected area.

A story of economics and the Danish state’s leasing of the area to entrepreneurs - Danish this time - who expanded and industrialised the quarrying operations; about asphalt replacing cobblestone paving and the massive stone crushers that for nearly half a century broke rock into rubble, which was used as an underlayer for asphalt paving or, in later years, mixed in with concrete; about accidents, silicatosis, market formations and tough competition until Hammerværket’s final day of operation in 1971; about nature’s reclamation of the scarred landscape.

The quarrying industry on Bornholm began with a German baron.

The quarrying industry on Bornholm began with a German baron.In 1884, he purchased the entirety of the land rights to the Hammerknuden promontory and established Bornholms Granitværk (English: Bornholm’s Granite Works) between the harbour Hammerhavnen and nearby lake, Hammersø.

The plant consisted of a large engine house with 16 forges, a drawing room, of-fice building and a tworesidence house for the foreman and mechanical foreman.

A special feature of the plant which distinguished it from others was a large stone cutting hall with carbonarc lighting and stone cutting shacks for the stonemasons.

A special feature of the plant which distinguished it from others was a large stone cutting hall with carbonarc lighting and stone cutting shacks for the stonemasons.Nearly all of the plant’s exports went to Germany until 1914, where the outbreak of the First World War put an abrupt end to the industrial venture.

Bornholm’s Granitværk ceased operations after the First World War.

Instead, the Danish government of the time leased out the quarry area to a Danish company, Møller og Handberg, resulting in a new surge of production at Hammerknuden.

The company constructed a large rock crushing plant in 1927, and in 1920 a large loading facility was constructed at Hammerhavn.

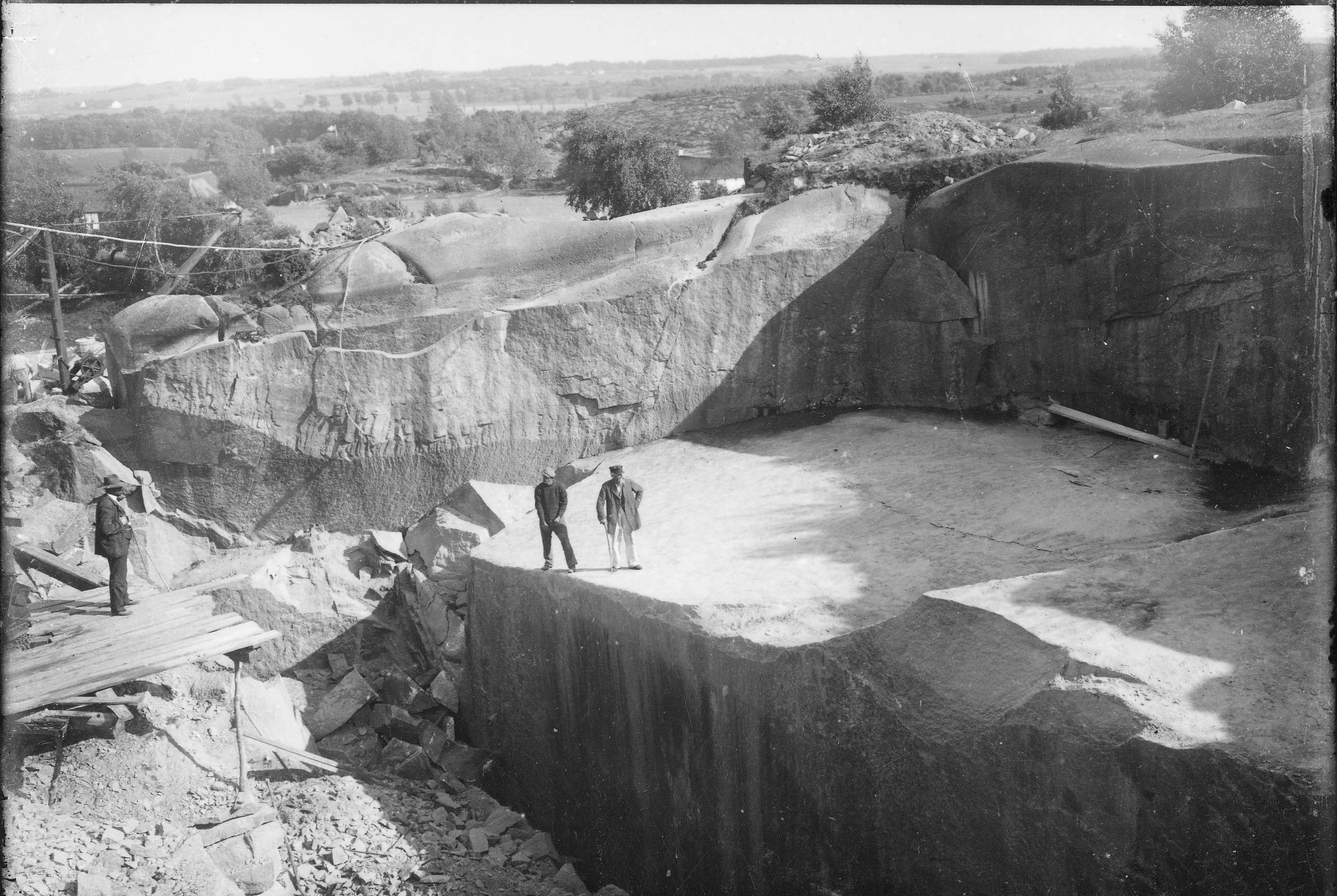

The company constructed a large rock crushing plant in 1927, and in 1920 a large loading facility was constructed at Hammerhavn.When Hammerværket ceased production in 1971, it became what is now known as Opalsøen (Lake Opal), a popular destination for athletes and others who enjoy rappelling and climbing.

In the summer, you can go on Denmark’s highest and longest cable car ride from the very top of the quarry across Lake Opal.

The working procedure was described thusly in 1920: “The crushing takes place at 22 metre-high elevations by means of demolitions that bring down 35,000 tonnes at once.

Large rocks are further demolished. The loading is done with a crawler excavator, and 6-tonne trucks with a special tipping system transport the rocks to the rock crushing plant located at the end of the quarry”.

Lake Opal is almost 10 metres deep and has formed out of the space where the quarrymen blasted the rock away.

The working procedure was described thusly in 1920: “The crushing takes place at 22 metrehigh elevations by means of demolitions that bring down 35,000 tonnes at once.

Large rocks are further demolished. The loading is done with a crawler excavator, and 6-tonne trucks with a special tipping system transport the rocks to the rock crushing plant located at the end of the quarry”.

Lake Opal is almost 10 metres deep and has formed out of the space where the quarrymen blasted the rock away.

Hammer Lighthouse is the highest point on the Hammerknuden promontory at 82 metres above sea level.

Hammer Lighthouse is the highest point on the Hammerknuden promontory at 82 metres above sea level.The lighthouse was constructed from local stones in 1872.

It generally works well but is often caught in local fog banks, which is less than ideal for a lighthouse.

A new lighthouse was therefore constructed soon after in 1895:

The Hammerodde Lighthouse, situated on the northernmost point of the promontory.

In the beginning, Hammerværket’s German owner had to bring in quarrymen from Sweden and Italy.

In the beginning, Hammerværket’s German owner had to bring in quarrymen from Sweden and Italy.They needed a place to live, of course, and so housing was built for them on the way leading up to the Hammer Lighthouse.

“Humlehodda” - the Humle Hut - was the first to be constructed.

It housed five quarrymen’s families, who lived in rather cramped quarters. The 1901 census listed 24 people living there.

There was a smithy in one end and a communal washhouse with a hand pump for the well and a large copper pot for big washes.

In one end of the washhouse were three oldfashioned outhouses with buckets that regularly needed emptying. No. 7 and no. 9 had their own outhouses closer to the house.

In the 1890s, two rows of workers’ dwellings were constructed in Sandvig.

In the 1890s, two rows of workers’ dwellings were constructed in Sandvig.Langelinie - or ‘The Long Row’ - had 20 dwellings, while Sandlinien - ‘The Sand Row’ - had 12.

The Moseløkken Quarry venture was started up by the local merchants Grønbech and Kurdts in the 1870s.

The Moseløkken Quarry venture was started up by the local merchants Grønbech and Kurdts in the 1870s.In the early 1900s, the quarry employed 50 workers.

The quarry is still in use today and periodically employs 2-4 workers.

At the quarry, the workers are able to produce very large and flawless stone blocks for construction projects.

The granite is especially suitable for monuments and sculptures.

At the Quarry Museum, you can learn about how the quarrying industry evolved over the past century or so, get a demonstration and explanation of the technique used by quarrymen on Bornholm and even try your own hand at stone cutting granite.